The progress of question / The question of progress

An urban design exploration on Live/Work for the Workforce

by Despo Thoma

In the early 1970’s Soho was considered a mecca of live/work, a refuge for struggling artists. New York City’s artist loft was widely romanticized, saw its glory in the 1970’s and its slow death after the 1982 Loft Law. Although the law was well intended and seeked “to regulate the conversion of certain buildings that were constructed for commercial and manufacturing use to lawful residential use”[1] it led to landlords pushing out tenants, or making them pay the cost of upgrading buildings. An exodus of low-income tenants which was completed with the siege of artist lofts by the real estate market. The so-called Soho Effect[2] poses an unsettling question for any kind of live/work exploration: where and how can affordable live/work spaces grow?

Section of the project mx.org: the industrial commons. Live or Work through public courtyards and service corridors,© Amritha Mahesh, Despo Thoma

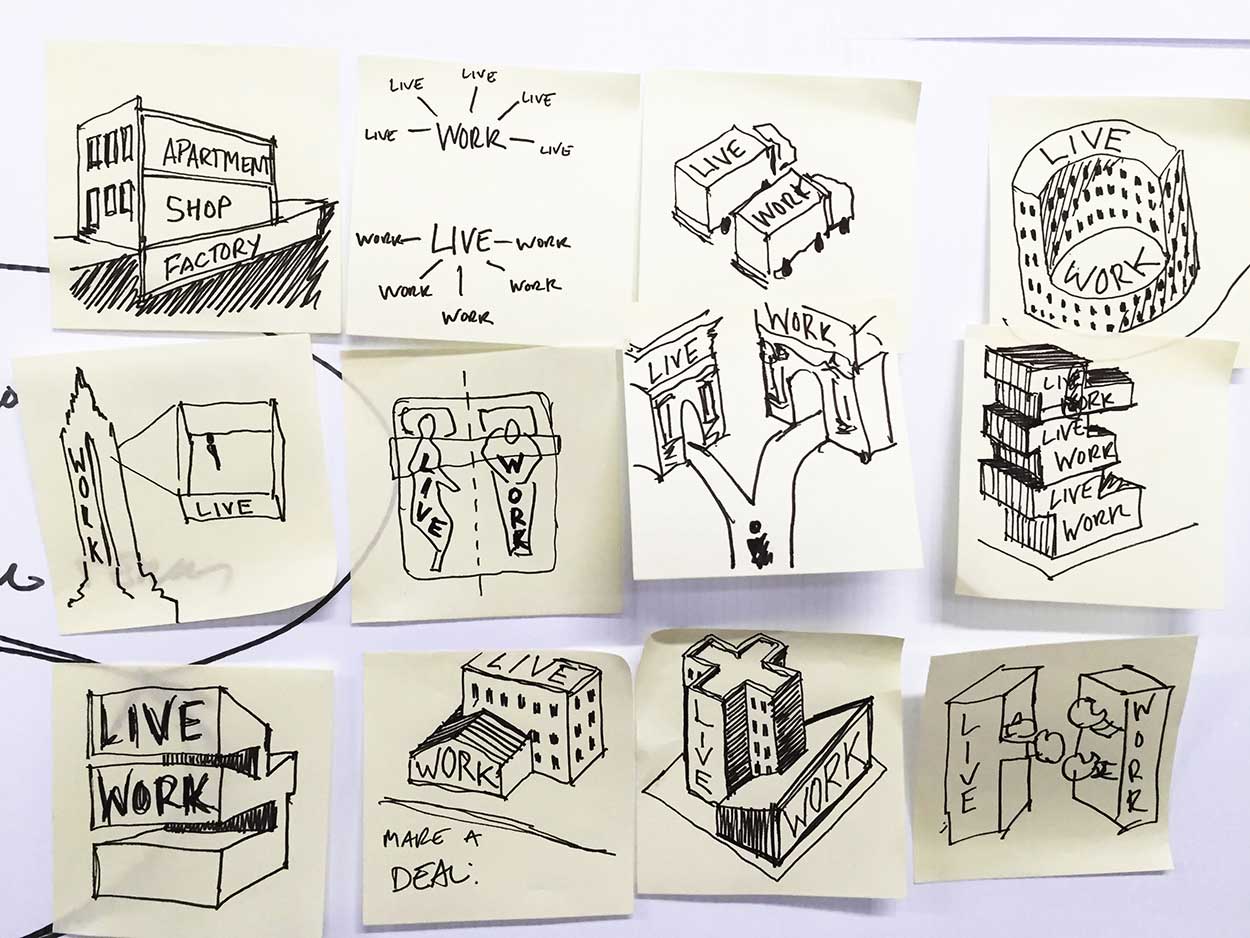

It has become commonplace nowadays, that the flexibility of live/work spaces offers not only spatial opportunities, but also economic and social ones, contributing to the growth of the creative class of the 21st century.[3] For architects and urban designers, the challenge of live/work becomes a critical one, especially in times when entrepreneurialism is cool[4]. For us – Thad Pawlowski, Amritha Mahesh and myself, the question of live/work for the workforce that the Institute for Public Architecture posed during our Residency there, soon transformed into to a question of affordable growth for the workforce.

The term “effect” used to described the change of Soho during the 1980’s implies a sequence in time, a pattern, the impact of an action in a certain place. Growth of a place seems to be followed by lack of affordability. But what happens if the place is not a static one, rather a moving one? Could the effects be avoided? The idea of exploring ways to foster live/work spaces on the move, spaces that steer away from the old pattern, became intriguing to us. Inevitably we posed ourselves the question: What industry lives and works nomadically?

FILM. We quickly laid our eyes on the film industry. Film as a nomadic operation, that moves between studio locations and neighborhood streets, appears to be an ideal industry for exploration of its live/work potential. It includes a wide range of working classes and a variety of expertise: from metalworkers, painters, hairdressers, to world-class directors and film actors. At the same time, the needs of a film production appear to be very similar to the ones of a healthy neighborhood: housing, working spaces, amenities and production offices, all flexible and in close proximity. From our perspective, film appears to operate as an industry-umbrella that requires diversity in skills and in spatial conditions, and as such it can be seen as a microcosmos of the city.

We started our IPA Residency at Sunset Park convinced that we had an idea of what live/work might mean for us, calling our team The Media is the Neighborhood.

Film productions range in scale and requirements: from one-person short films, to independent films, to large scale film productions. Resources, such as space and equipment are not easily available to independent filmmakers that do not have a major studio supporting their endeavor. The idea of creating a film hub that could be stationed as an anchor in the neighborhood provided the opportunity to envision film operations rather than a quick migration of experts, a concentration of resources for the community that could double as film production support mechanism.

Industries like film could operate as a neighborhood patron, coupling two of the goals Mayor de Blasio posed for the coming years: to create more affordable housing and to promote more NY-made film productions. According to the Office of Media and Entertainment[5], goal of the Mayor is to advance and spark more NYC-based film productions taking advantage of New York City’s iconic landscape and at the same time foster local economies. All in light of finding ways to ensure community growth while providing affordable housing[6].

In conversations with Bill Amenta from Industry Lighting and Laura Gahrahmat from Eastern Effects Movie Studio during our IPA Residency, it became clear to us that industries like film have the potential to act as an anchor in a neighborhood and help foster small local businesses in a sustainable way. But the bottom line is that the decision needs to be made by directors and producers changing the normal mode of operation: is it going to be a parade of huge trailers occupying the streets of the neighborhood, or is there a way for the resources to be found in the neighborhood itself?

Laura Gahrahmat pointed us towards Jodie Foster’s example[7] as a director of the movie Money Monster. During the shootings in downtown Manhattan, Jodie Foster and the rest of the production team chose to accommodate actors and crew in nearby hotels and give them coupons for restaurants in the area, rather than filling the streets with actor trailers, catering and other amenities. An action that gain the support of the Mayor as it can be a productive way to couple neighborhood growth with film production. Why isn’t this happening more often then?

We question our own question once again. Our live/work design exploration lead us first to a spatial and demographic analysis of the film industry and it redirected us again to now focus on anchor industries and their economic and social role in neighborhoods. As seen from Jodie Foster’s paradigm, solutions exist if those that need to make the call have a motivation to do so. The challenge, for us, once again transformed from a spatial one, to a socioeconomic one: how can we promote development of mission-driven industries over money-driven industries?

The question of mission over money it’s not a new one. It has been at the core of any kind of collective social endeavor that tries to break out from the siloed modes of operation. In conversation with Abby Subak from Art Gowanus, it became clear that non-profit organizations are the ones who can play a central role in preserving and growing jobs in the arts and industries. Similarly, visiting Red Hook and speaking with Dustin Yellin, artist and founder of Pioneer Works, it was evident that collaboration across different fields is one most important challenges of today’s society.

JOBS. New York City has added 500,000 private sector jobs in the last five years[8], the fastest rate of growth since such statistics have been collected in the 1970s. Most of these new jobs are in Manhattan below 59th street; however, there is also significant job growth in places like Long Island City, Williamsburg and Downtown Brooklyn. These are also neighborhoods that have seen a steep escalation in the value of land[9] and the overall cost of living, leading to a growing displacement of the working population. In other words, jobs are growing in the expense of blue collar jobs especially in communities of color. Once again, the question we ask ourselves as designers is transformed again: Who is the industry for? Who is the neighborhood for?

To further deepen our understanding of industrial jobs and manufacturing areas, we looked at MX zones that indent to mix Residential and Industrial uses, and we spoke with Elizabeth Yeampierre from UPROSE in Sunset Park. Looking at communities of color that are trying to grow in a sustainable way next to an industrial waterfront, facing the challenges of climate change was revealing to us. From the perspective of the community, allowing residential in manufacturing areas drives up land values and leads to displacement of small businesses and affordable housing. Something that puts many against any effort for mixing live and work. On the other hand, Nina Rappaport, author of the Vertical Urban Factory, saw the potential of a live/work research project like this to investigate further how vertical factories can provide jobs in dense urban settings. Evidently, the city’s industrial zones and their future is a testament of the way New York City will choose to treat blue collar communities.

THE COMMONS. The contrast between what the communities need and how development occurs in a neoliberal world is striking, especially today. Is it even possible to envision a mission driven development that fosters the growth of industries and gives leverage to communities? We met with Avi Telyas from Makerhoods and Pablo Castro from Obra Architects to see how they – from a developer’s standpoint – understand incremental growth in communities. For them the answer lies in providing space to grow economically on site while ensuring a profitable investment. The question for us became then clear: How does a 21st century industrial commons look like, and how does it become appealing to a developer?

Our research has eventually allowed us to narrow down to one single challenge: how can we empower local communities to become stakeholders of their future? Focusing on the Gowanus, we proposed a new way of governing and implementing through our project mx.org: the industrial commons. We argued for a new model of development and a potential new zoning district with consequent building typology. A model that would create a pathway for existing residents and businesses to have a stake in the value creation they bring to their community.

In order to do so, the notion of distributing ownership and sharing resources is critical. We proposed a new set of rules that would impose maximum lot sizes and minimum unit counts. Each unit would have access to public and service courtyards in order to benefit for the common assets of the neighborhood and also have responsibility over it. The key to this form of development is the existence of a local entity, where uses and local regulations would be adjusted specifically to the needs of the neighborhood. Regulations and laws can be relaxed or enforced accordingly and at the same time the local entity would be responsible for the buildings being up-to code. The success of such endeavor lies on the premise that the commons and their rules of governance come from the community itself and are not imposed from outside.

The progress of trying to ask the right question has highlighted our research and it is evident through the project. It is certainly not an end point, rather than a moment of a continuous exploration on industries, affordable growth and community empowerment. Until the exploration of the next question.

First published from Institute for Public Architecture

[1] http://www.nyc.gov/html/loft/html/laws/loft-law.shtml

[2] http://blogs.cornell.edu/art2701mja245/2013/06/16/the-soho-effect/

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creative_class

[4] http://www.economist.com/node/13216053

[5] http://www1.nyc.gov/site/mome/index.page

[6] www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/631-16/mayor-de-blasio-nyc-sets-affordable-housing-record-highest-production-since-1989

[7] http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20160520/ENTERTAINMENT/160529991

[8] https://www.labor.ny.gov/stats/nyc/

[9] http://www1.nyc.gov/site/finance/taxes/property-assessments.page