NEOPTOLEMOS MICHAELIDES / HOUSE IN NICOSIA

by Haris Hadjivassiliou, Architect

‘L’auteur original ne pas celui qui n’imite personne, mais celui que personne ne peut imiter’ – Chateaubriand

Neoptolemos Michaelides is widely regarded as the father of twentieth century architecture in Cyprus.

He studied at Milan Polytechnic during the 1940’s, and developed an understanding and appreciation of the contemporary Milanese avant garde architectural scenes. These undoubtedly had a strong bearing on the formation of his own autonomous architectural process, as seen throughout his life’s work.

In Cyprus, his legacy comprises a large number of important modern buildings dating back to the early fifties, each one a master class in poetic simplicity and honest structural expression. It is for these attributes that his architecture is greatly appreciated in his homeland. His true originality lay in the adaptation of indigenous building types and the use of natural, local materials to create something new. One of his most important completed buildings is residential: a house, designed and constructed in Nicosia during the mid sixties for himself and Maria, his artist wife. The project’s typology is a progressive variation of the residential types seen in his earlier work, but this particular building is a tour de force. The construction is subtle, the use of form both sophisticated and refined. The design approach is ‘critically regionalistic’, a position that many architects would later adopt.

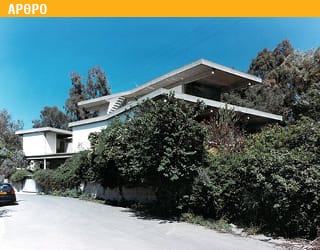

The project’s form and ‘gestures’ are dictated by the elongated site on which it rests. Upon seeing this villa for the first time, one soon experiences its power to transfix and wonders at its inherent beauty. It is a home like a Minoan palace: majestic and yet humble; complex yet beautifully plain. It appears almost to float above the horizon, cushioned softly in its verdant surroundings. The receding white walls and projected grey slabs create horizontal zones and give the space its human and generic scales, which titillate the eye. There is a regularity, a rhythm to its structure and a refined, measured proportion to its composition.

It is worth noting the variety at play across the villa’s three storeys. The parking spaces and quests living areas at ground level contrast a far more reserved second floor, the piano nobile, comprising living quarters for the owners. The third floor, an isolated den for study, is crowned by a beautifully articulated at the top slab parabolic vault, thus completing the villa’s intrinsic classical components: base, torso, and crown. These are connected by flights of marble steps embedded in concrete that irrevocably draw any visitor to ascend, to experience the pure drama of the vertical space. Impressive collections of art and artefacts are seamlessly integrated into the domestic space. Patios and terraces penetrate or extend from the interiors to complement external conditions: the sun’s arc or a cool breeze.

Maximum use was made of local materials, which have maintained their natural colour and texture. The building’s reinforced frame, walls and ceilings are fair-faced concrete. Their moulds were meticulously fashioned and sandblasted so that the finish reveals the rich pattern of the timber surface. The external cavity walls and internal partitions are hollow brick plastered with lime mortar and white marble sand, a traditional technique used to waterproof walls and vaulted Church roofs. There is not a single drop of paint used.

Natural light pours in through carefully controlled openings, enlivening the fair-faced texture and transforming the interior into a relaxed, almost mystical space. It is worth noting the architect’s intelligent use of detail: the wooden balustrade, left in its natural form, which grows more beautiful with age; the double-faced artefact displays; the protruding concrete gutters, which became a trademark in his later work.

On a theoretical level, the architect had no interest in elevations, as he once stated. The rational yet poetic plan formed his basis. Things were made beautiful through honesty, refinement, and purity. This principle draws from modern philosophical, even oriental, thinking. Michaelides and his fascinating wife used to travel to Japan and Korea in the sixties, a rarity among Cypriots. For those fortunate enough to have known him, it was clear that the principles he applied to architecture and those he applied to everyday life were the same: his architectural philosophy was born out of his day to day experience, rather than any adherence to stylistic fashions. Looking more deeply at the structural elements of his work one can easily draw a parallel to the structural principles of Le Corbusier’s Maison Domino and The Five Points of Modern Architecture, but then these manifestos and Michaelides’ work hail from similar times; times when a search for new ideas in the construction of reinforced concrete was the norm. These were the times of masters like Nervi and Ponti, about whom the young architect must have been aware during his time in Milan. At any rate, the result in this case is a sophisticated house that relates to, and integrates with, its physical and personal environment, and this is where its true value lies.

Haris Hadjivassiliou

The article was originally publidhed in magazine Domus – December 2014 – Neoptolemos Michaelides / House in Nicosia