LAURENCE BURT: IN MEMORIAM

by Haris Hadjivasiliou, architect

A retrospective exhibition and funeral gathering was held on Friday May 15th at the York cemetery Chapel to celebrate the life and work of the late Laurence Burt.

Laurence Burt, a gifted artist, an inspirational teacher, and a profound humanist died peacefully at home on 26th April 2015, aged 90.

He was born in Leeds, United Kingdom in 1925 and, although he was trained as a metalworker, he developed a deep interest in artistic expression and went on to study art at Leeds College in 1955. Soon after leaving school he established himself as one of the most original British modernist sculptors, while lecturing in various UK Art Schools and Polytechnics.

At this early stage he began to explore, via sculpture, the cosmic qualities of his time: the concepts of the space age condition. The medium for his first creative work was, inevitably, plain sheet metal, hammered and welded into shape. The intrinsic qualities of the medium paired with his early preoccupation gave birth to a series of evocative helmets, first exhibited in Drian Gallery, Marble Arch. The Arts Review of 1964 called them: “The machines and gear of a science fiction that is rapidly becoming fact. A space helmet which is at the same time an alien temple. His imposing and sweeping form are equally suggestive of an instrument, a device, and of an organic entity…It is indicative of Burt’s outstanding stature among younger sculptures that his work can make such allusions whilst at the same time possessing the true qualities of sculpture being undeniably present as form, volume and mass”.

Curators and critics expressed a serious admiration for this powerful work, which prophesied a new age of astronautical explorations and their intellectual implications for humankind. What is remarkable is that Burt moved on to produce a completely autonomous body of work reconciling symbol and form with great honesty, a characteristic evident in all his later work. We must remember that the 1960’s brought many theoretical art revolutions, producing local (North Yorkshire) masters like Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, of whom the young artist must have been aware.

After a serious emotional crisis, Burt’s odyssean journey moved him on to new realms of work with the same creative spirits that profoundly communicated his thoughts: “I delved into innumerable books on psychology, philosophy, the esoteric religions, and the writings of early Christian mystics. With hindsight I see that it was the beginning of a long and difficult search for some kind of personal belief”.

A high point in his life came in 1972 when, along with his artistic partner in life, Angela (a historical costume designer and producer), he settled in Famagusta, Cyprus. There, he established a local avant garde gallery and working studio.

Those Cypriot sun-filled mornings gave him peaceful time to reflect upon his latent preoccupation: the quickly changing scenes to which modern man was not prepared to adapt. As he writes in a 1974 brochure accompanying his work: “technology and scientific developments have given us much to be thankful for but also much that is alarming; the speed at which innovatory events happen takes ones breath away. Change is our basic problem. The sooner we can come to terms with this idea and accept it as a concept or a working hypothesis, the sooner will we solve some of our difficulties”.

Laurie soon became known and got involved in the local art scene. He began mixing with a number of prominent local artists such as Votsis, Aloneftis, Hughes, Kouroussies, Parashos, Savva, Valentinos etc, with whom he shared sensibilities, motivation, and a British educational background. Some became lifelong friends.

Following his philosophical challenges he found himself working quietly in his old one-room garage towards defining the essence of his new work. This gave birth to a series of modern icon reliefs and sculptures that were caught between the then and now: they possessed the power and principles of the indigenous medieval icons, while reinventing them for a modern viewer. Charles Spencer, the former editor of Art and Artists in London wrote of the works: “I find it fascinating that in his own special way he responded to the indigenous culture of Cyprus in a series of images which are best described as “modern icons”… in turning his back on the West he has consciously sought a new, less restrictive working environment and an audience less conditioned by accepted art concepts.”

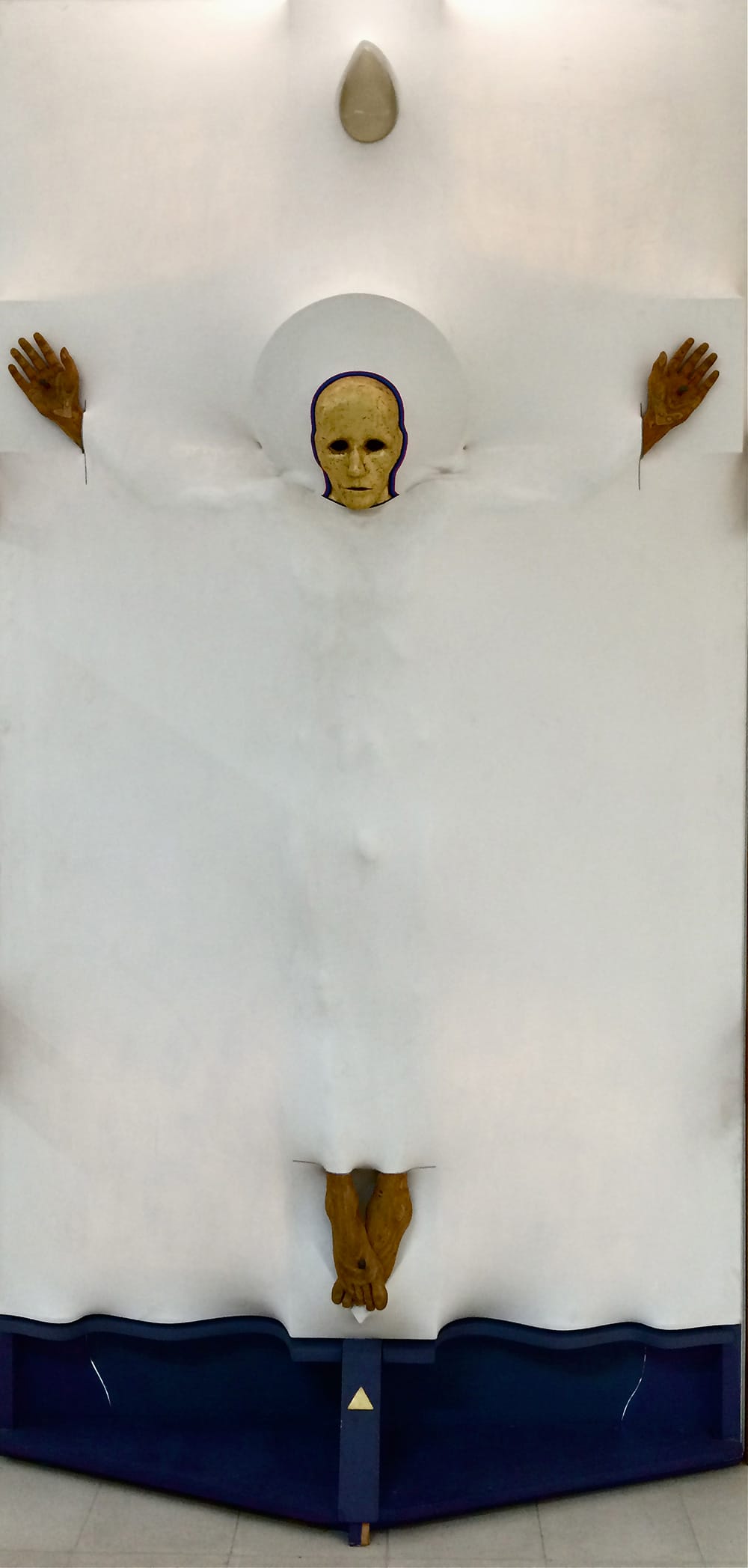

Laurie’s “icons” move us with their modern spirituality and substance, artistic beauty and the power to transfix. Constructing and detailing these media reliefs and sculptures was masterfully done by way of stretching synthetic fabric over intricately shaped substructures. The fabric was then PVC painted white to create dramatic contrasts of light and shade, adding to the “icons’” profound spatial dimension. Just as in architecture, “God is in the details”: these works are delicately charged with symbolism, their parts subtly articulated to give true meaning to the whole. As Burt states: what is “quite important is that the unfilled eye sockets retain their blackness which formally, by the resulting emptiness, adds a certain symbolic mystery of expression which I always felt added to the spirituality of the work”.

By “empty eye sockets”, Burt generally refers to the small number of icon faces he produced while in Cyprus. However, this particular quote refers to his most impressive work: “The Piscean”. This life-size modern crucifix, like the other Famagusta works, was made by stretching synthetic fabric but, unlike its siblings, is of uniquely monumental proportion and power. It is a novel and dynamic work which challenges the beholder with deep existential questions.

Solomos Frangoulides, a local art critic in Nicosia commented in Haravgi March 1974: “I wonder if this work represents a crucifixion or a visual return from the unknown, which is beyond death. Because this figure, which is at once a reality and a dream, is a portrayal of an equivocal meaning and is the expression of pathos as well as of a triumphant apparition from on high. I discern here his tortuous path in the midst of matter that he has determined to conquer, and the intellectual content that through it he sets out to express. I see his infinite respect for tradition, his deep knowledge in the manipulation of materials, the sensitivity in the delineation of the human form, the beauty of proportion. I see plainly that he has gone through a stage of profound soul searching and that he is something of a mystic in his study and application of conventional method. He has neither compromised nor capitulated”.

The Piscean was bought by the Archibishop Makarios’ advisers to be housed in the future theological college, a project which never materialized due to the ’74 invasion. It was then presented in a group exhibition (Votsis, Kouroussis and Chrysochos) at the Argo Gallery in February 1974. Today, after a lot of wandering, this fascinating piece can be seen at the Makarios Foundation and Cultural Center in Nicosia.

Dr Eleni Nikita, art historian and critic, comments: “Burt is the artist who brought back to the Cypriot artistic scene a renewed human figure, a figure featured in a series of works under the general title “Modern Images”. Contrary to his figurative Cypriot colleagues, Burt draws his inspiration from the legacy of Cypriot cultural tradition and especially byzantine hagiography, producing very personal works”. (Catalogue for the 1997 exhibition “Cypriot Art 1950-74: The British Connection”)

On his return to Britain, Burt assumed a teaching post for six years at Falmouth School of Art, becoming part of the artistic environment of Cornwall, then moving again in 1980 to the historical centre of medieval York. The York years expanded the spectrum of his work. He experimented with diverse art forms, like the Japanese haiku, juxtaposing it with minimalistic paper collages, a feast for the eye and intellect.

He never abandoned his fascination with metal and, in his tiny studio, he produced small, mysterious sculptures of remarkable delicacy. He no longer had to deal with the structural concerns of his previous, larger works. Instead, he concentrated more on defining their articulating elements (sometimes resulting in kinetic sculptures), which translated memories and experiences in a more autonomous way, through recognizable subjects that retained a greater semblance of reality. In these small sculptures he demonstrated an enthusiasm for art and myth either from medieval York or the Kantara castles and Greek history of Cyprus. Some of these compositions were placed in plexiglass boxes or metal cages, creating the three-dimensional equivalent of a picture. Unlike earlier work these possessed their own spatial environments, miniature worlds protected from reality by these invisible or visible veils. An integral common element is a leaning ladder with distorted perspective, which alters the scale of the work. Through this distortion, its form jumps to colossal dimensions, conveying the anguish and hope that always haunted Burt’s creative imagination; the nature of modern man; his helplessness against the proud era of so-called progress; and his hope for a spiritual renewal through a revitalised philosophy of faith…

In relation to one of Burt’s exhibition Things Out of Mind at the Roslyn Lyons gallery in 2005, Dr Jon Wood of the Henry Moore Institute comments: “At the core of Burt’s work is a constant preoccupation with things dynamically caught between past, present and future, between inner and outer space. It was a preoccupation that is articulated in all kinds of ways in his oeuvre, from solid welded metal sculpture to interactive game playing. This can be seen from the early Helmet works which combined medieval warrior with NASA astronaut to create a powerful image of the ‘black box’ of the human mind, to the participatory ‘telepathic’ games of his CAM PSI project. Such works also remind of us of the company Burt has kept over the years and how easily he moved between the realms of traditional sculptors (Dalwood, Sandle, Wall. Boden, Smedley, Kenny etc) and those of artists concerned with cybernetics, systems of control and interactivity (Willats, Ascott etc). Burt has a rare ‘billingual’ ability here: not only conversant between such positions, practices and media, but also making works that show some important and insightful connections between them. Traditional sculpture and conceptual art come together, in a sense, in Burt’s work. It is certainly one of his most important achievements, and, perhaps, it will be one of his most important legacies too”.

Burt exhibitions include: John Moores Exhibition, Walker Art Gallery Liverpool (1959); ‘Construction England’, the Drian, London (1961); Profile III, Englische Kunst der Gegenwart’, Bochum, (1964); ‘The Inner Image’, Grabowski’s, London, (1964); ‘Portrait of a Man in a Hurry’ (Apollinaire), I.C.A. Gallery, London (1968); ‘Painting Performances’, Arts Lab, Druny Lane, London, (1969); One Man Exhibition: ‘Propaganda for Control’, Angela Flowers Gallery, London, (1971); ’11 Sculptors One Decade’, Arts Council Touring Exhibition (1972); ‘Four into One’, Gallery Argo, Nicosia, Cyprus (1974); ‘Sculpture of the Blind’, Tate Gallery, London (1976); ‘Transformation Review’, Angela Flowers Gallery, London (1978); One Man Exhibition: ‘BITS’, The Gallery, Falmouth, Cornwall (1979); One Man Exhibition: ‘An exhibition of small Monuments and Biographical Notes’ Arts Council, Oriel Gallery, Cardiff, (1980); ‘British Sculpture in the 20th Century’, Whitechapel Gallery, London, (1982), British Art Medal Society Commission: Margitte Medal (1983); ‘XX F.I.D.E.M.’ Stockholm, Exhibition of Modern Art Medals, (1985); ‘Records of work placed in Tate Gallery Archives, London (1991); ‘Haikus and Images’, Waterstones Booksellers, York, (1993); ‘Collage’ an exhibition of pictures and word, Alcuin College, University of York, (1994); ‘Revolutions – 1950 – 1960 – 1970, Three Decades of Art, Music, Cinema in Cyprus’, Nicosia, (1997); Library Exhibition, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, (2004); One Man exhibition, “Things out of Mind’, work past and present, Roslyn Gallery, University of York, (2005); ‘Relationships – Contemporary Sculpture’, York Art Gallery, (2007); ‘British Surrealism in Context – A Collector’s eye’, Leeds City Art Gallery, (2009); Tate Britain, Millbank, Birthday Exhibit (Helmet 1, 1962), (2010); Connections and the Surrealisms in Cornwall, Falmouth Art Gallery (2010).

His Work is held in various public art institutions and private collections including: Arts Councils of Great Britain and Wales; The Tate Britain, London; Gulbenkian Collection, Wales; Contemporary Art Society, Wales; Collection La’Casse, Paris; Leicester Schools Collection; Muzeume Naradowe, Warsaw, Poland; Pefkios Georgiades Collection, Nicosia; National Collection of Cyprus, Nicosia; Henry Moore Institute, Leeds; Falmouth Art Gallery, Cornwall; Henry and Ruth Sherwin Surrealist Art Collection, Yorks; Archbishop Makarios Collection, Cyprus and various other public and private collections in Britain and abroad.

Haris and Andreas Hadjivassiliou

The article was published for the first time in The Cyprus Weekly – May 22, 2015 – Laurence Burt: In Memoriam